The Nuclear Resister – March 20, 2021 by Marion Pack

The Flawed History of US Plutonium Pit Production – Do we really need them?

This issue of The Nuclear Resister provides more information on the history of plutonium pits. It makes the case for why we don’t need new plutonium pits. Tell President Biden we need to end the arms race, not throw fuel on it by developing new weapons.

Now is the time to act!

President Joseph Biden

The White House

1600 Pennsylvania Ave.

Washington, DC 20500

Website: whitehouse.gov/contact

Comments: 202-456-1111

The Flawed History of US Plutonium Pit Production – Do we really need them?

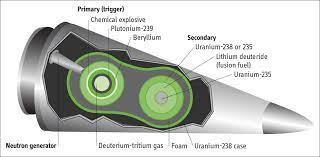

The heart of a nuclear bomb is called the “plutonium pit.” A hollow metal core weighing only several kilograms, the plutonium pit’s initial explosion starts the chain reaction in a nuclear weapon. 1 It is the heart of a nuclear bomb.

Nonetheless, pit production has been riddled with safety and environmental problems. Here, we will take a look at some of them.

The U.S. produced the first plutonium for nuclear weapons in Hanford, Washington in 1944. However, production of the plutonium pit didn’t begin until 1952 at a facility in Rocky Flats, Colorado. The Rocky Flats facility was closed in 1989 due to widespread contamination, repeated safety violations, and negligence. The site was classified as one of the most polluted sites in the country. Clean-up began there in the 1990s. Eventually pit production was relocated to Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, but that lab was not properly equipped for mass production and it struggled to produce more than a few pits a year.

The drive to produce more pits, however, didn’t evaporate; and, under the Obama administration, nuclear modernization plans opened the door for new plutonium-pit production. In the 2015 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), Congress required the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) to build a facility that could produce at least eighty plutonium pits per year.

FYI: The budget for nuclear weapons does not come out of the defense budget as many people assume, is part of the Department of Energy. The NNSA is a semi-autonomous arm of the Department of Energy. Thus, it is able to hide costs that should be part of the already bloated Defense Budget, which receives much more attention.

In 2019, under the Trump Administration, the push for pit production increased. Congress ruled that by the year 2030, 80 plutonium pits per year must be produced. No longer was it okay to simply show the capability of producing that many each year; they had to actually do it. (In contrast, the Obama Administration had considered several plans for new pit production at Los Alamos, but they were all set aside because of unclear justifications or budget shortfalls.)

For the fiscal year of 2021, NNSA requests $1.4 billion to support pit production. This is a huge increase from the prior year’s $570 million. With that initial funding, the NNSA is moving ahead with plans to build not one, but two facilities—one at Los Alamos and another at Savannah River Site in North Carolina. According to budget analysis by the Congressional Budget Office, in January 2019, the NNSA building plans on the two sites are estimated to cost $9 billion over the next decade.2 However, past performance by the NNSA raises questions about whether they can deliver on time and within budget.

The NNSA argument for producing more pits rests on two assumptions. The first is that our plutonium pits are aging and the second is that newer pits will be safer. The most frequent argument focuses on the viability of the U.S. stockpile as warheads age.The current U.S. arsenal is estimated to include about 3,800 warheads, of which 1,750 are currently deployed, the remainder is in reserve in various stages of readiness.12

So how old is too old for a pit? In the early 2,000s, NNSA considered building a capacity for producing between 125 and 450 pits per year. The weapons lab argued that the pits will perform as designed for 45 to 60 years. 4 In 2012, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory went even further putting pit lifetimes at 150 years.

The U.S.-Russian New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), which limits each country from deploying more than 1,550 strategic warheads, was set to expire in February. Fortunately, President Biden moved swiftly and reaffirmed the treaty for another five years. That’s a good start, but if we want to eliminate the danger of nuclear war, we need to increase pressure on the Biden Administration.

Over 50 countries have signed the Treaty on the Abolition of Nuclear Weapons. Regrettably, none of those countries are the ones that have nuclear weapons. U.S. plans to replace aging plutonium pits with new ones reveal U.S. enthusiasm for expanding its nuclear arsenal—and that encourages other nuclear-armed countries to do the same. The only way forward is to eliminate nuclear weapons completely.

We need to pressure President Biden to stop a new nuclear-arms race now. President Biden must take leadership by taking the first step and signing the Treaty on the Abolition of Nuclear Weapons. He must also encourage the other nuclear nations to do the same. By working together, we can have a nuclear-free future.

President Joseph Biden is making policy decisions now. Make your voice heard! Let President Biden know how you want him to the critical issue of nuclear weapons today!

The White House

1600 Pennsylvania Ave.

Washington, DC 20500

Website: whitehouse.gov/contact

Comments – 202-456-1111

1. U.S. Department of Energy, “FY 2021 Congressional Budget Request: National Nuclear Security Administration,” DOE/CF-0161, February 2020, p. 163.

2. Congressional Budget Office, “Projected Costs of U.S. Nuclear Forces, 2019 to 2028,” January 2019, p. 5, 2. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2019-01/54914-NuclearForces.pdf.

3. For stockpile estimates, see Hans M. Kristensen and Matt Korda, “United States Nuclear Forces, 2020,” 12. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Vol. 76, No. 1 (2020): 46–60

4.Arnie Heller, “Plutonium at 150 Years: Going Strong and Aging Gracefully,” 16. Science and Technology Review, December 2012, pp. 12,14